The global shift toward net-zero buildings and climate-resilient infrastructure has positioned renewable energy integration at the forefront of engineering design. Among the suite of clean energy solutions, geothermal energy stands out as a reliable, highly efficient, and perpetually available resource. Unlike intermittent sources such as solar or wind, the Earth’s constant subsurface temperature offers baseload thermal energy for heating, cooling, and hot water, making it a foundation for true energy independence. This deep dive explores the technical application, challenges, and digital pathways for integrating geothermal systems into the modern built environment.

The Physics of the Loop: Geothermal Energy in Action:-

At its core, harnessing geothermal energy in building design revolves around the principle of the Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP). This system capitalizes on the fact that, below the frost line, the Earth maintains a stable, moderate temperature typically between 50°F and 60°F (10°C and 15°C) year-round, regardless of surface weather conditions. The thermal gradient between the surface and the ground provides the perpetual energy source we tap into.

Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHP): The Engineering Core:

A GSHP is fundamentally an electrified mechanical system that moves thermal energy, rather than creating it through combustion. In winter, the system extracts heat from the ground via a circulating fluid (usually a water/antifreeze mixture) in a closed-loop piping network, concentrates that heat using a vapor-compression cycle, and delivers it to the building’s HVAC distribution system. In summer, the process reverses: the system extracts heat from the indoor air and rejects it into the cooler Earth, providing highly efficient air conditioning. The efficiency of this exchange is measured by the Coefficient of Performance (COP), which often ranges from 3.0 to 5.0 meaning for every unit of electricity consumed, the system delivers three to five units of thermal energy.

Horizontal vs. Vertical Systems: Site-Specific Design:

The engineer’s first major challenge in a geothermal project is site investigation and loop-field configuration. The choice between horizontal and vertical loop fields is governed by available space and subsurface geology.

Horizontal Systems are typically cheaper and faster to install, requiring shallower trenches (usually 4 to 8 feet deep). However, they demand a significant amount of land area, making them generally unsuitable for dense urban sites. The design must account for the proximity of pipes to each other and to other utilities, while also ensuring the system is placed deep enough to avoid major temperature fluctuations caused by seasonal surface weather.

Vertical Systems are the go-to solution for urban projects, utilizing boreholes drilled deep into the ground (often 150 to 500 feet or more). This method minimizes the above-ground footprint but carries higher drilling costs and requires extensive geotechnical analysis. The engineer must carefully consider drilling logistics, rock type, thermal conductivity, and the potential for boreholes to interfere with the structural foundations of the building or adjacent properties.

Economic and Environmental Imperatives for Renewable Energy Integration:-

The engineering justification for geothermal extends far beyond mere compliance; it presents a compelling case for financial and environmental leadership.

Lifecycle Cost Analysis and ROI:

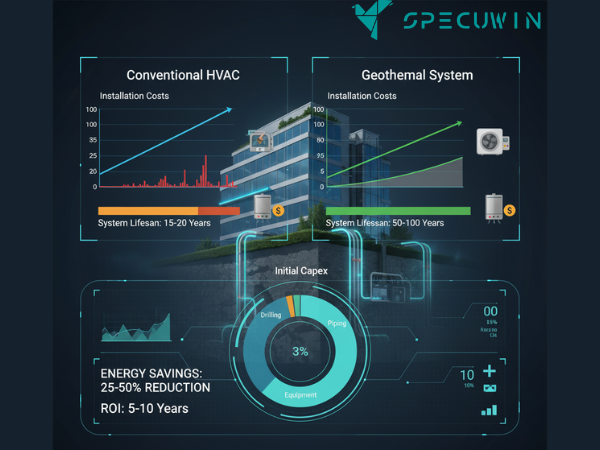

While the initial capital expenditure for a geothermal system is often higher than a conventional HVAC system, the long-term operational savings are significant. Engineers must utilize lifecycle cost analysis (LCA) to demonstrate the system’s return on investment (ROI). This analysis incorporates factors such as:

- Installation Costs: Drilling, piping, and mechanical equipment.

- Maintenance Costs: GSHP units require less maintenance than boilers and chillers, which are exposed to harsh outdoor conditions.

- Energy Savings: The core benefit, often yielding 25%–50% reduction in heating and cooling energy use.

- System Lifespan: Ground loops have an expected lifespan of 50 to 100 years, far exceeding conventional equipment.

By running comprehensive energy simulations, engineers can provide clients with a clear payback period, often making the business case irrefutable over a 10-to-20-year horizon.

Decarbonization and Energy Independence:

The most critical imperative is the environmental benefit. Geothermal heat pumps use electricity only to move heat, meaning their carbon footprint is tied directly to the source of electricity. As grids transition to cleaner sources, the geothermal system becomes progressively cleaner, ultimately achieving net-zero emissions. For the engineer designing a high-performance, future-proof building, integrating geothermal is a foundational step toward decarbonization. This is why the larger context of Renewable Energy Integration is so important in modern construction. Geothermal systems dramatically reduce peak load demand and are not reliant on the volatile fossil fuel market, securing genuine energy independence for the structure.

Engineering Challenges in Geothermal System Design:-

Successful geothermal implementation hinges on overcoming specific site and design challenges that require specialized engineering expertise.

Soil and Geology: The Crucial Site Investigation:

The thermal performance of the loop field is directly proportional to the thermal conductivity of the subsurface materials. A detailed geotechnical survey is non-negotiable. Engineers must:

- Conduct Thermal Conductivity Testing (TCT): A field test where a thermal probe is inserted into a test borehole to measure the rate at which heat moves through the ground.

- Analyze Stratigraphy: Understand the layers of soil, rock, and groundwater, as this dictates drilling methods and costs.

- Manage Groundwater: The presence and flow of groundwater can significantly impact thermal transfer and must be accounted for in system modeling to prevent thermal plume creation.

Ignoring these steps can lead to an undersized system and a phenomenon known as thermal drift, where the ground temperature slowly shifts over years of operation, degrading system efficiency.

Sizing and Performance Modeling:

The engineer must carefully size both the ground loop and the heat pump capacity. Undersizing the loop field forces the heat pump to use supplemental, less-efficient heating/cooling, negating savings. Oversizing wastes capital. Modern engineering relies on sophisticated modeling software to:

- Balance Thermal Loads: Account for the cumulative heating and cooling loads over a full year to ensure the ground temperatures stabilize over time.

- Model Building Interaction: Simulate the thermal interaction between the building’s envelope, internal loads (occupants, lighting, equipment), and the GSHP system.

- Iterative Design: Adjust bore depth, spacing, and loop configuration to find the optimal balance between cost and performance.

BIM and Digitalization: Optimizing Sustainable Building Design:-

The complexity of geothermal systems makes them a perfect candidate for digital integration, leveraging Building Information Modeling (BIM) to streamline design, coordination, and facility management. BIM serves as the central hub for optimizing Sustainable Building Design through geothermal technology.

Integrating GSHP into the BIM Model:

BIM allows the mechanical engineer to precisely model the complex network of subterranean piping and mechanical equipment, integrating it seamlessly with the building’s structural and architectural data. This is crucial for clash detection—preventing the loop field from interfering with foundations, utility trenches, or landscaping. Furthermore, the BIM model acts as a repository for essential data, such as TCT results, borehole logs, and pump specifications. The ability to integrate this technology with advanced modeling tools like BIM and CoBie is vital for closing the information gap between design, construction, and building operations. This comprehensive digital twin ensures that the as-built documentation is accurate, which is indispensable for long-term maintenance and performance validation.

Achieving Net-Zero Through Smart Systems:

Geothermal systems are key enabling technologies for zero-energy and net-zero buildings. When combined with a highly efficient building envelope and on-site renewable energy generation (like solar PV), they push the structure’s energy use to a minimal baseline. The residual energy demand is then easily offset by renewable generation. The engineer’s goal is to optimize this relationship, using the geothermal system as the foundation of efficiency. This is directly tied to the ultimate goal of achieving a Zero-Energy Building Design. Smart building control systems are used to monitor the performance of the GSHP and the ground temperature in real-time, allowing for predictive maintenance and continuous commissioning to ensure the system consistently operates at its peak COP, validating the initial engineering assumptions.

Conclusion:-

The implementation of geothermal technology is a prime example of successful Renewable Energy Integration a non-negotiable practice for engineers committed to sustainable building design. From the initial geological survey and thermal modeling to the final integration within a BIM environment, the engineering effort required is meticulous and multi-disciplinary. Yet, the reward is a building that is quieter, safer, less reliant on fossil fuels, and substantially cheaper to operate over its life cycle. Geothermal is not a niche technology of the future; it is the proven engineering foundation for the resilient, sustainable building design we must construct today.

FAQ’s:-

1. What is the average Return on Investment (ROI) for a commercial geothermal system?

A. The ROI for a commercial geothermal system typically ranges from 5 to 10 years, primarily due to the 25% to 50% reduction in annual heating and cooling costs and the lower long-term maintenance needs compared to conventional HVAC systems.

2. Does geothermal energy work in all climates and geological regions?

A. Yes, geothermal energy is effective in virtually all climates because the Earth’s temperature below the frost line remains relatively constant year-round, regardless of surface air temperature.

3. What is “thermal drift” and how do engineers mitigate it?

A. Thermal drift is the gradual, year-over-year change in the ground temperature around a geothermal loop field, often caused by an imbalance between the heat rejected (cooling) and heat extracted (heating). Engineers mitigate this by performing detailed annual thermal load balancing during the design phase and, in some cases, by incorporating supplementary heat rejection methods, such as cooling towers, to manage excess heat.

4. How is BIM (Building Information Modeling) utilized specifically for a Ground Source Heat Pump (GSHP) project?

A. BIM is used to precisely model the subterranean loop field and the interior mechanical components, enabling clash detection with structural elements and utilities. It acts as a central data repository for thermal conductivity test results and provides a crucial visual and data model for facility managers during the operations phase.

5. What is the expected lifespan of a geothermal ground loop?

A. The ground loop piping, which is typically made of high-density polyethylene (HDPE), is chemically inert and highly durable. Its expected lifespan often exceeds 50 to 100 years, making it a nearly permanent asset that far outlasts the mechanical heat pump unit itself (typically 15-25 years).

Read More On:-

For more information about engineering, architecture, and the building & construction sector, go through the posts related to the same topic on the Specuwin Blog Page.

Find out more accurately what we are going to take off in the course of applying leading new technologies and urban design at Specuwin.